The Johnson family settled near Campbellville in the 1800s and were profiled in The Canadian Champion in 1931. Reading this article now gives us insight into how black people were represented in media in the 20th century.

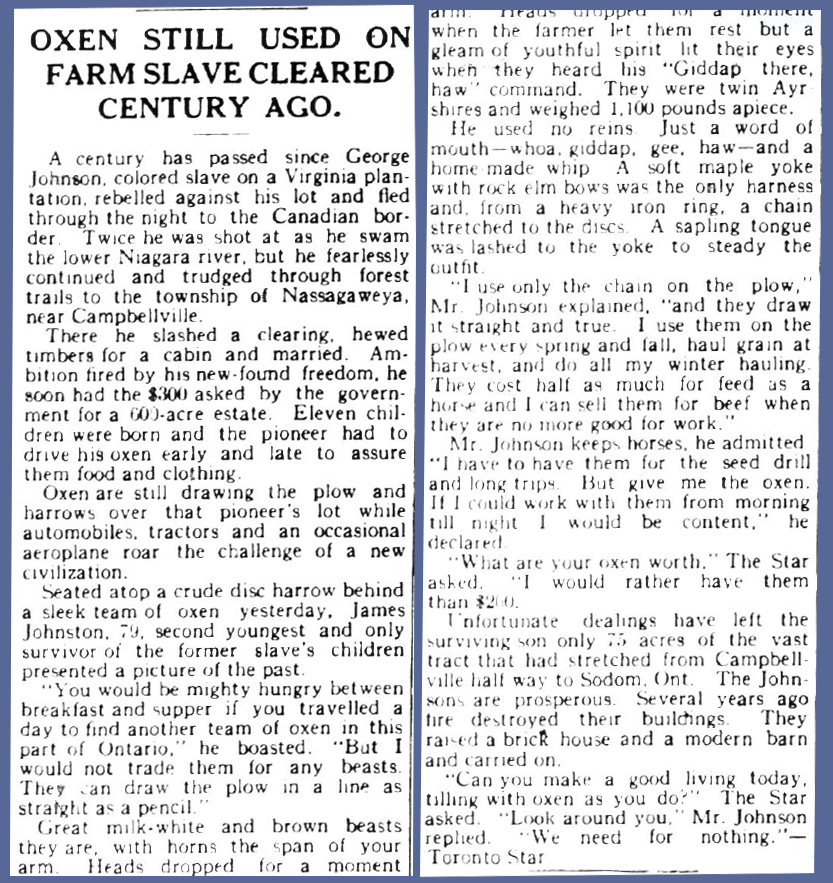

This news story reads:

A century has passed since George Johnson, colored slave on a Virginia plantation, rebelled against his lot and fled through the night to the Canadian border. Twice he was shot at as he swam the lower Niagara river, but he fearlessly continued and trudged through forest trails to the township of Nassagaweya, near Campbellville.

There he slashed a clearing, hewed timbers for a cabin and married. Ambition fired by his new-found freedom, he soon has $300 asked by the government for a 600-acre estate. Eleven children were born and the pioneer had to drive his owen early and late to assure them food and clothing.

Oxen are still drawing the plow and harrows over that pioneer's lot while automobiles, tractors and an occasional aeroplane roar the challenge of a new civilization.

Seated atop a crude disc harrow behind a sleek team of oxen yesterday, James Johnson, 79, second youngest and only survivor of the former slaves' children presented a picture of the past.

"You would be might hungry between breakfast and supper if you travelled a day to find another team of oxen in this part of Ontario," he boasted. "But I would not trade them for any beasts. They can draw the plow in a line as straight as a pencil."

.... Unfortunate dealings have left the surviving son only 75 acres of the vast tract that had stretched from Campbellville half way to Sodom, Ont. The Johnsons are prosperous. Several years ago fire destroyed their buildings. They raised a brick house and a modern barn and carried on.

"Can you make a good living today, tilling with oxen as you do?" The Star asked. "Look around you," Mr. Johnson replied. "We need for nothing."

The writing used 90 years ago can be very unfamiliar. Journalists' choices of language can hide or obscure certain things, or emphasize others, in ways that we now may not understand.

What, for example, does the journalist mean by "rebelled against his lot" in the first paragraph? We know that George Johnson was a slave and that he escaped his slavery. His "lot" would then be the conditions of slavery - but the word used to indicate someone's fate, chance, or fortune. Was slavery a "chance" event? Was it George's "misfortune" to be captured or born into slavery?

What might the Johnson family's "unfortunate dealings" have been, in the second-to-last paragraph? The article means that the family must have needed money and was forced to sell their land, or that the land was taken from them somehow, or perhaps they found that the land was too much burden or caused them trouble in some way. Knowing what we know about the way white people treated black people from the 1850s to the 1930s, can we guess what the "unfortunate dealings" may have involved?

Research done since this article was written in the 1930s shows that the Johnson family had 200 acres originally, not 600 acres. It also shows that George Johnson purchased this land in 1828. We can also say that there were two George Johnsons, a "Little George" and a "Big George," who may have travelled together when they left the United States, but definitely settled together outside Campbellville.

It seems that James Johnson, the person quoted in this article, was the son of Big George, and that he and his wife Clarissa took excellent family records that helped the researchers of this article.

Little George, who was not James's father, was the original purchaser of the property. Both Georges were involved in the founding of the St. John's Anglican Church across the road, which was a part of the small black community there from 1842 onwards. A stone church built in 1913 remains there now. But the article doesn't specify if the Johnson family still owns land across the street.