"When they first went to the camps, they were housed in tents left over from the American Civil War," said Skeoch. "The Civil War was in the 1860s. They had no stoves. There was a lot of frostbite, but not many died while they built the shacks they would live in."

Seven hundred hard-core Japanese resisters, along with thousands of German prisoners-of-war, were sent to Angler Camp in northern Ontario, near Marathon, where large red targets were painted on the backs of their jackets — so they'd be easy to shoot if they ran. Some who weren't rounded up successfully passed themselves off as Chinese.

[Rena Matsumoto Anderson, 50, of Mississauga]'s father was in Angler while her mother had finished high school and taught in the camps.

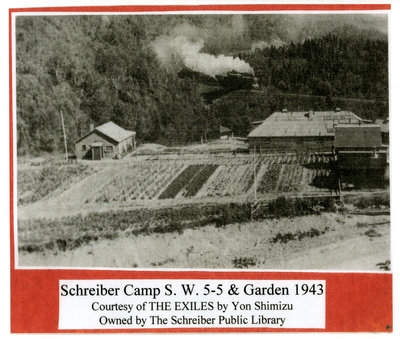

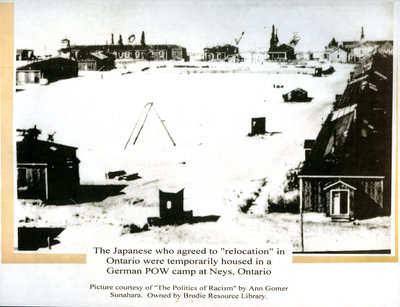

Many work camps in Ontario were tents at first, and most never graduated past drafty, shoddily-built shacks. In some places houses and work buildings were converted into dormitories where many men were crammed into small living quarters shared with each other. One, near Marathon, Ontario, was a former prisoner-of-war camp that had held German soldiers and was repurposed. In Angler, Ontario, a new prisoner-of-war camp surrounded with barbed wire contained any person of Japanese descent who resisted the RCMP's orders and directions.

Those who were moved to Ontario to work and live met with harsh opposition from most existing communities.

According to one scholar, the most vocal opposition to Japanese-Canadian workers in Ontario was in Chatham - "the plan was hotly debated in city council meetings, with opponents citing the treacherous nature of the Japanese as the main reason for their opposition." The town tried to have all citizens of Japanese descent forcibly removed from the region. Residents signed a petition to ensure the workers weren't housed inside city limits; others tried to limit the number of workers allowed to come into town at one time - this was set at 10, and they had to be accompanied by an RCMP constable.

In Dresden, a petition to the premier said "they can never become real Canadians. That once here they would stay" - among other reasons not to admit the workers. In Essex, workers were forbidden from entering town at all. In Glencore, the work house under construction was vandalized by a group of local boys, and all the windows were smashed.

In Beamsville, a farm that uses exiled workers was threatened by having a cross burnt on its lawn. In Port Dalhousie, a city official threatened to drive Japanese Canadians off its pier into Lake Ontario.

“The presence of Japanese,” some argued, “tends to lower the rate of wages and standard of living in the community.”

... “There’s a farmerette camp on the

Tregunno farm,” pointed out Reeve Sheppard of Niagara Township to R. F. Clarke, manager of the St. Catharines office of the National Selective Service, “would you or I want our daughters at that camp?” Clarke responded that his daughter “went to school with Japs,” and he would therefore not be opposed. Charles Daley, Ontario’s Minister of Labour, who represented Lincoln in the

Provincial Parliament, however, agreed with Sheppard. “I do not see how you can put farmerettes on the same place with Japs even if you keep the camps apart. They’ll be working together on the same farm.”

Religious organizations provided the sole welcoming committee to exiled workers. They often brought donated books and leisure activities, supplied the camps with food when the workers first arrived, and offered them religious services.

Support came out more broadly for the use of exiled labour when white Ontarians realized just how much of a labour shortage they were facing - many farmers and companies faced financial ruin if crops were left unharvested. In May of 1942, the mayor of Kent sent a personal message of welcome to the Schreiber labour camp to invite workers to come and harvest sugar beets. Attitudes also changed when the Japanese workers showed they had skill and a strong ethic:

By all accounts the farmers were greatly impressed with the Nisei labourers, and toward the end of the harvest season, began to vie with each other for their labour."