Emily Pauline Johnson (1861-1913), most commonly referred to as Pauline Johnson, is a poet, writer, singer-songwriter, and performer who was born in Six Nations territory near current-day Brantford, Ontario, six years before Canada became a nation. Her Mohawk name is Tekahionwake, which translates to "double life."

Her father was a Mohawk clan chief and her mother was of English descent, whose family had immigrated to the United States in the 1830s. Pauline and her three siblings were brought up to respect both cultures. However, because British law recognizes heritage through the father's family, they were considered Mohawk; because Indigenous communities recognize heritage through the mother's family, they were considered English by the Mohawk community and therefore not members of a tribal clan.

Pauline was educated at home instead of at the nearby Mohawk Institute, one of the first Canadian Indian residential schools. Her respect for English literature came from spending long hours reading in her family's library.

Pauline's first creative outlet was writing and performing in local amateur theatre. Her first published poem was "My Little Jean," published in the New York Gems of Poetry.

After her father died in 1884, Pauline was able to support her mother and sister through her income from poetry and plays.

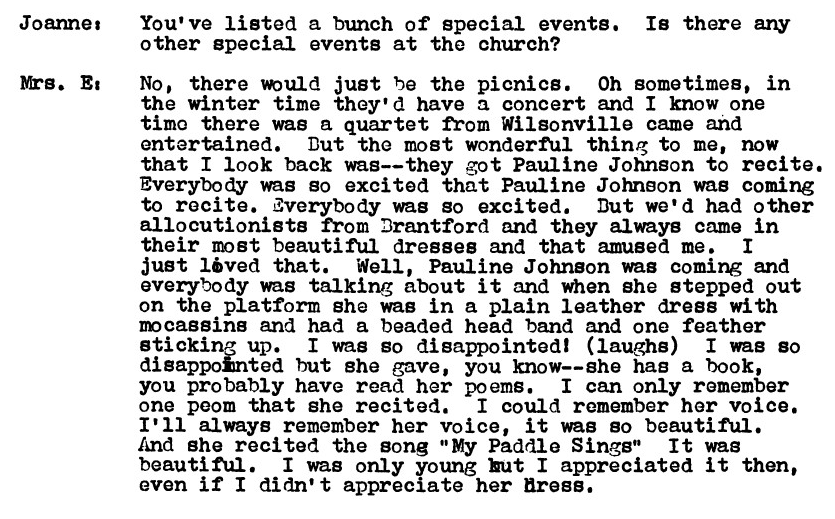

Pauline was very shy about reading her poetry in public, usually asking others to recite for her at events. In 1892, she recited her poem "A Cry from an Indian Wife" at an event called the Canadian Authors Evening in Toronto; she was the only woman performing that night, and the only author asked to give an encore.

After this triumph, she performed in public more frequently, often wearing a costume inspired by Mohawk aesthetic elements. Sometimes she would change back and forth from an English style of dress to an Indigenous style during intermission, depending on the type of poem she was reciting.

For example, read this poem, "A Cry from an Indian Wife":

My forest brave, my Red-skin love, farewell;

We may not meet to-morrow; who can tell

What mighty ills befall our little band,

Or what you'll suffer from the white man's hand?

Here is your knife! I thought 'twas sheathed for aye.

No roaming bison calls for it to-day;

No hide of prairie cattle will it maim;

The plains are bare, it seeks a nobler game:

'Twill drink the life-blood of a soldier host.

Go; rise and strike, no matter what the cost.

Yet stay. Revolt not at the Union Jack,

Nor raise Thy hand against this stripling pack

Of white-faced warriors, marching West to quell

Our fallen tribe that rises to rebel.

They all are young and beautiful and good;

Curse to the war that drinks their harmless blood.

Curse to the fate that brought them from the East

To be our chiefs—to make our nation least

That breathes the air of this vast continent.

Still their new rule and council is well meant.

They but forget we Indians owned the land

From ocean unto ocean; that they stand

Upon a soil that centuries agone

Was our sole kingdom and our right alone.

They never think how they would feel to-day,

If some great nation came from far away,

Wresting their country from their hapless braves,

Giving what they gave us—but wars and graves.

Then go and strike for liberty and life,

And bring back honour to your Indian wife.

Your wife? Ah, what of that, who cares for me?

Who pities my poor love and agony?

What white-robed priest prays for your safety here,

As prayer is said for every volunteer

That swells the ranks that Canada sends out?

Who prays for vict'ry for the Indian scout?

Who prays for our poor nation lying low?

None—therefore take your tomahawk and go.

My heart may break and burn into its core,

But I am strong to bid you go to war.

Yet stay, my heart is not the only one

That grieves the loss of husband and of son;

Think of the mothers o'er the inland seas;

Think of the pale-faced maiden on her knees;

One pleads her God to guard some sweet-faced child

That marches on toward the North-West wild.

The other prays to shield her love from harm,

To strengthen his young, proud uplifted arm.

Ah, how her white face quivers thus to think,

Your tomahawk his life's best blood will drink.

She never thinks of my wild aching breast,

Nor prays for your dark face and eagle crest

Endangered by a thousand rifle balls,

My heart the target if my warrior falls.

O! coward self I hesitate no more;

Go forth, and win the glories of the war.

Go forth, nor bend to greed of white men's hands,

By right, by birth we Indians own these lands,

Though starved, crushed, plundered, lies our nation low…

Perhaps the white man's God has willed it so.

Johnson was also able to make money writing articles for newspapers and magazines, such as this 1985 article published in Harper's Weekly and reprinted throughout the world, describing the cultures and lifestyles of Iroquois communities. Johnson asserts that

A century of insidious inroads made by white settlers, of a civilization not always wisely conducted, has despoiled the Iroquois of his game, his national glory and hardihood, and the greater portion of his real estate, inasmuch as the reserve has dwindled and shrunken into a comparative dot of land that embraces but 53,000 acres of the least value along the entire course of the river. In early times much of this land slipped out of the Indian's possession in an unrecorded manner but after a season, when incoming whites were settling the country, the demand for river lands in southern Upper Canada grew urgent, and the Iroquois were induced to surrender their reserve bit after bit ....

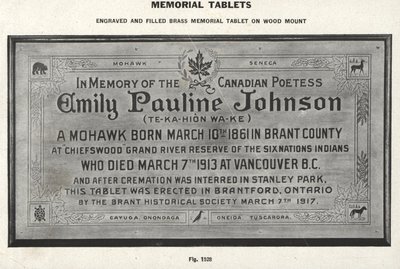

Pauline Johnson died of breast cancer in 1913, at the age of 51. In 1961 the Canadian Post Office chose Pauline Johnson as the first woman born in Canada to have her likeness depicted on a stamp.

The house where she grew up is now Chiefswood Museum, a commemorative space to explore materials related to Johnson's legacy, and a National Historic Site. Outside the museum sits an Ontario Historical Plaque about Johnson's life.

Johnson was made a Person of National Significance in 1945; there is a monument to her in Vancouver; several public schools are named after her.

Pauline has always been considered a complex artist, whose family heritage influenced her work to become a unique combination of Indigenous and settler perspectives, stories, and loyalties. On stage, this played out literally with her changes of costume, embodying both cultures; in her work, she gives the world sometimes conflicted, sometimes clever takes on race, gender, and heritage.