Reconnection

For more than a century, continuous instability and atrocities in China was the main factor that encouraged people to move to foreign lands to seek shelter and avoid uncertainty. However, the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 marked China's growing stability: mass social movements were prohibited and the Communist government reformed itself to embrace the idea of capitalism and free trade. These changes in Chinese society were generally welcomed by its population as more economic opportunities began to emerge. However, it was crucial for Chinese Canadians because this allowed them to reconnect with their homeland without censorship and regulations, while able to even making economic ties. Michael Chan is a Chinese Canadian politician who is dedicated to representing Chinese immigrants in Ontario. This speech by Michael Chan refers to Ontario's economic ties with China.

Human Rights & Political Expression

The increasing contact with Canada and the rest of the western world, especially with Chinese immigrants who have lived in the west for generations, brought a cultural shock to the younger generation in mainland China. One of the most significant influences is the idea of political expression, as China remained a heavily censored society where individual expressions were unimaginable. For those immigrants who lived in Canada for decades and suffered from racism, immigration restrictions and communal isolation, travelling to China and witnessing political oppression from the Communist regime makes them realize the unfairness Chinese people and its oversea diaspora were treated politically.

Starting in the late 1970s, the idea of political liberation began spreading both in China and among the Chinese Canadian communities. The constant flow of communications across the Pacific helped more and more people to realize the need to express themselves politically. In Canada, Chinese migrant communities began presenting themselves as a significant social and political force to combat discrimination and communal restrictions imposed on them for decades. Many people started running for offices, and organizing labour unions and public assemblies; the era of communal expression and political participation had finally begun.

China's growing stability combined with embracing the global market, and free trade further encouraged people to start their own entrepreneurship for a chance at prosperity. Starting in the 1980s Chinese immigrants in Canada began growing slowly: yet this time, most people were aiming for economic opportunities as they sought to run businesses in Canada. All across Ontario, whether in metropolitan Toronto or downtown Chinatown, the presence of Chinese culture saw a mass increase. Many people at this time decide to travel alone to Canada in a more frequent manner, while many Chinese Canadians decide to visit China after almost decades of separation from their homeland. This created a flow of information, cultural connections and economic ties between China and Chinese Canadians. Rather than staying within a communal network, Chinese Canadians often connect with their homeland in various different ways. With the economic reopening in 1978, China's enormous population became an attractive market for new business entrepreneurs seeking opportunities all around the world--many of them were second-generation Chinese Canadians.

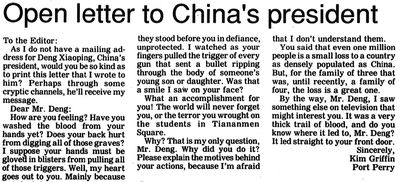

Similar social changes also occurred in China at the same time, thanks to the increasing flow of contact. However, the social movement in China quickly caught the attention of the Communist regime and resulted in a bloody massacre in 1989. On June 4th, 1989, the Communist regime ordered its military to brutally suppress students and intellectuals who held a mass demonstration in the capital city of Beijing, demanding democratic reform. The incident, later known as the "Tiananmen Square Massacre," drew the world's attention, and especially concerns and sympathy from Chinese Canadian communities who were also struggling for their own rights. For the first time, settlers organized assemblies and demonstrations in Ontario, condemning violence and expressing their concerns for those who lost their lives during the massacre. This also marked the beginning of Chinese immigrants connecting with their homeland beyond family and cultural heritage, as younger generations continued to support social liberation since 1989, making Chinese communities one of the most active forces in Canadian democracy in general.